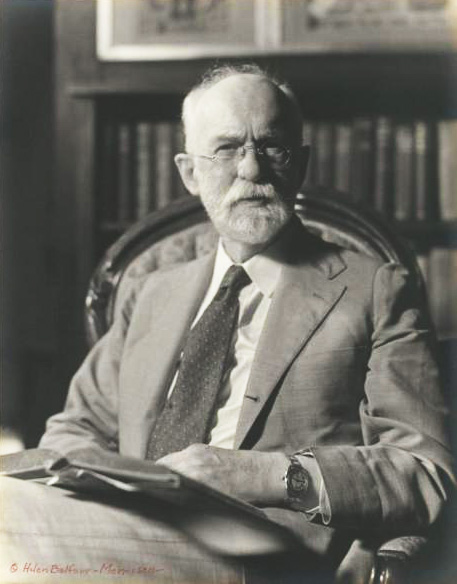

On March 26 1867, Chicago architect, conservationist and civic leader, Dwight Heald Perkins was born. He is one of my greatest heroes, and my birthday twin (different years, of course!), so I am devoting this April blog to him.

Portrait of Dwight Perkins by Helen Balfour Morrison, 1935, courtesy of Morrison-Shearer Foundation, Northbrook, Illinois

Dwight Perkins should be a “household” name to anyone in the Chicago area who loves architecture, nature, or learning about the Progressive Era. But he has received far less scholarly or popular attention than many of his associates and friends, such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Jens Jensen, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahony Griffin (Dwight’s cousin), who have been recognized for their contributions to architecture, landscape architecture, conservation efforts, urban planning, and art in the Midwest. Although Dwight’s accomplishments to these fields are extraordinary, he has largely been overlooked.

There has been some scholarship devoted to Dwight’s work. H. Allen Brooks provides brief descriptions of his work in The Prairie School: Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwestern Contemporaries. Several colleagues and I highlighted some of his school architecture on chicagohistoricschools.wordpress.com. Perkins Woods in Evanston, a small 7-acre nature area, is named in Dwight’s honor. Still, Dwight H. Perkins deserves much more. I am writing this short biography in tribute to him in hopes that others will become inspired by his contributions.

Dwight Heald Perkins was from an educated and accomplished family. Abraham Lincoln appointed his father, Marland Leslie Perkins, as Judge Advocate for the state of Tennessee. Marion Heald Perkins, Dwight’s mother, was a social reformer with close ties to Jane Addams. However, Dwight’s childhood was not easy; his father’s early death forced Dwight to quit school in the eighth grade. In an unpublished manuscript entitled Perkins of Chicago, his daughter, Eleanor Ellis Perkins, explains that Dwight’s first job at the Chicago stockyards put him in danger because he had to carry weekly payroll money from the bank to the packinghouses. He quit and found a job as an office boy at a local architectural firm, thereby discovering his path in life.

Corkery School, ca. 1940, courtesy of Bill Latoza

Several years later, Dwight borrowed money from a family friend to study architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He did well, graduating in just a few years, and he briefly taught there afterwards. While in Boston, he met his future wife, Lucy Fitch Perkins (1865 – 1935), a talented artist who would eventually become one of America’s most popular children’s authors. The couple settled in Chicago and Dwight went on to work in the office of Chicago architect and planner Daniel H. Burnham.

In 1894, Dwight formed his own firm with the commission to design an office building for the Steinway Piano Company on Van Buren Avenue. After the building’s completion, Dwight leased its two upper stories, opening his office there, and subleasing space to other young talented architects, including Irving and Allen Pond, Robert Spencer, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahony Griffin. Even Frank Lloyd Wright worked out of Steinway Hall for a few years. Scholars believe that the friendly spirit in the loft of Steinway Hall help spur what is now considered the “Prairie School.”

Penn School, ca. 1908, courtesy of Bill Latoza.

Dwight was appointed chief architect for Chicago’s Board of Education in 1905 after receiving a nearly perfect score on the civil service exam and a letter of recommendation from Burnham. Although concerned about the pressures of corruption that had driven out his predecessors Normand Patton and William Bryce Mundie, Dwight was hopeful that things had changed. After all, Jane Addams had become a member of the School Board.

Dwight made major improvements to school buildings by adding more natural sunlight, widening stairwells and hallways to minimize crowding, and placing bathrooms on every floor (when toilet rooms had previously only been in basements). He designed dozens of beautiful new buildings, such as Cleveland, Lloyd, Pullman, and Trumbull elementary schools and Carl Schurz High School, saving money by eliminating expensive cut-stone embellishments.

Carl Schurz High School, ca. 1970, courtesy of Bill Latoza.

But any expectations about an honest school board were quickly dashed. By 1910, the school board wanted him out, accusing him of “incompetence, extravagance and insubordination.” He refused to resign. When the board scheduled a hearing, Dwight insisted the proceedings be made public. The entrenched corruption was quickly exposed, and Dwight came off as a local hero in prolific newspaper coverage of the trial.

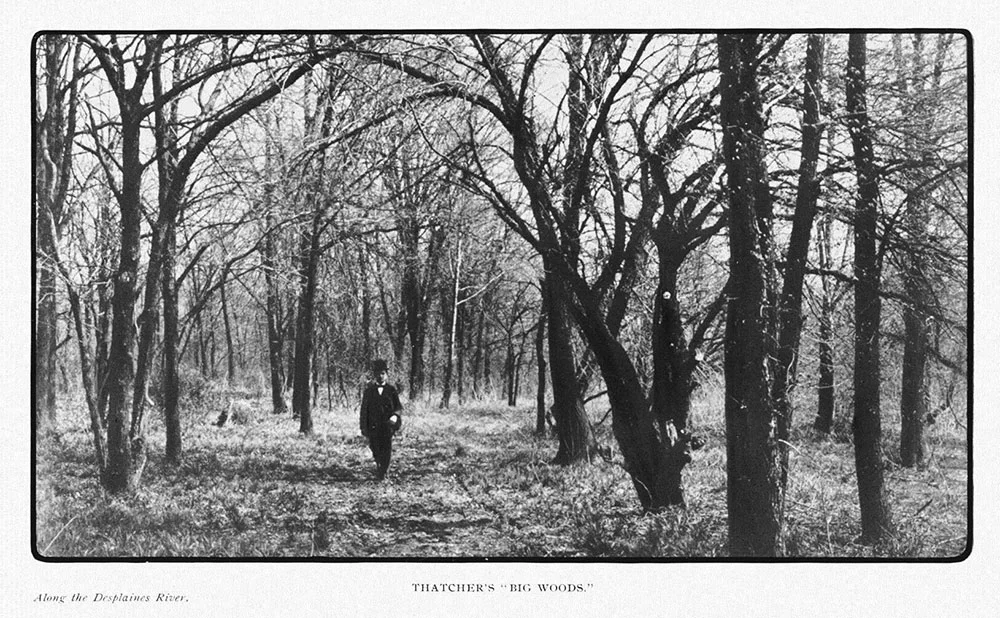

“Thatcher Woods,” from The 1904 Report of the Special Park Commission to the City Council of Chicago on the Subject of A Metropolitan Park System, by Dwight H. Perkins and Jens Jensen.

Throughout the drama of the Board of Education trial, Dwight was involved with another topic fraught with politics. He and his friend, Jens Jensen (1860-1951), a Danish immigrant and landscape architect, had first envisioned a Forest Preserve system at the turn of the 20th century. The two published a remarkable document recommending the ambitious system entitled The 1904 Report of the Special Park Commission to the City Council of Chicago on the Subject of A Metropolitan Park System.

Café Brauer, ca. 1930, Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

There were many obstacles to realizing Dwight’s dream of a Cook County Forest Preserves system. Legislation to form the Forest Preserves passed in 1905, but proved to be inoperable. A second bill, drafted in 1909, was deemed unconstitutional by the Illinois Supreme Court. Throughout the years, Dwight continued working behind the scenes – impressing friends, colleagues, and politicians with the importance of saving the vast scenic lands at the outskirts of the city for future generations. Finally, a new bill was drafted and approved by voters in 1914. Dwight worried that the third bill might not hold up against another court challenge. He begged his friends to initiate a lawsuit and when no one agreed, he realized he’d have to do it himself. According to his son Larry Perkins, Dwight was delighted when he lost his case on April 20, 1916. The failure to win his lawsuit, meant that the Cook County Forest Preserves could be established.

Lion House, Lincoln Park Zoo, 2010, Julia Bachrach.

Dwight Heald Perkins died on November 2, 1941. Today, Dwight’s legacy includes a nearly 70,000-acre system of forests, wetlands, and prairies; beautifully-designed schools in and beyond Chicago; several Lincoln Park structures, such as Café Brauer; and many other noteworthy buildings throughout the Midwest.