John Warner Norton painted this arched panel as part of his 1914 Early Explorer mural series in the Fuller Park Field House. Photo by James Iska.

Like many Chicagoans, I’m pleased every time I see new examples of outdoor murals throughout the city’s neighborhoods. I especially enjoy discovering large colorful murals on underpasses or other structures that would be, if left unadorned, stark and dreary. While the city’s outdoor mural movement has been unfolding for several decades, Chicago had an important earlier tradition of interior murals. Many of these artworks were created or inspired by John Warner Norton, a talented painter, illustrator, and teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Along with producing sensational murals of his own (some of which remain today), the influential Norton trained student artists, including several women who went on to have impressive careers in art.

John Warner Norton from John Warner Norton by Jim L. Zimmer, 1993.

Born into one of Lockport, Illinois’ wealthiest families, John Warner Norton (1876- 1934) attended private preparatory schools before entering Harvard University as a law student in 1895. He had to return home in January of 1897 without completing his studies because his father’s business had failed. After briefly taking classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Norton decided to head west. At first, he worked as a tutor in California, but then moved onto an Arizona ranch, where he became a cowboy. When the Spanish American War erupted in 1898, the young adventurer went to Florida and joined Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, serving as a member of Troop C, 1st United States Volunteer Calvary.

Teddy Roosevelt and His Rough Riders, 1898. Library of Congress.

The Cliff Dwellers’ “Navaho” mural by John Warner Norton. Photo courtesy of The Cliff Dwellers.

In 1899, Norton returned to Illinois, and to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied under renowned teachers including John Vanderpoel. Norton took classes alongside female students, as art was one of the few fields considered acceptable for well-to-do women at the turn-of-the-century. John Warner Norton began courting a classmate, Margaret “Madge” Washburn Francis. In 1903, John and Madge were married in her parents’ home in Rock Island, Illinois. Over the next few years, Norton supplemented his income as a painter and illustrator by teaching at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts.

In the early 1900s, as the mural movement was growing throughout the nation, John Warner Norton began producing his earliest murals. Among them was “Navaho,” a painting he created for the Cliff Dwellers Club, a private cultural organization made up of writers, architects, and visual artists, including himself. Initially dubbed the Attic Club, the group selected the Cliff Dwellers name in early 1909. John Warner and Madge Norton had spent some time in Arizona early in their marriage, and his various sojourns in the American Southwest may have, at least in part, inspired his painting of a dignified Native American family from that region. Norton went on to paint many other murals in and beyond Chicago. Among them were large interior paintings in the Fuller and Hamilton Park field houses and the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Midway Gardens, a popular but short-lived entertainment venue. His out-of-state commissions included artworks for county courthouses in Iowa and Minnesota.

John Warner Norton’s mural for Midway Gardens, ca. 1914. Courtesy of Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Art Institute of Chicago.

Around 1910, Norton joined the faculty of the Art Institute of Chicago and began working closely with Thomas Wood Stevens (1880 – 1942), the head of the Institute’s illustration department and an instructor in the new mural department. In order to provide practical experience in mural painting, the Art Institute made arrangements with various organizations and locations to have students decorate interior spaces. For example, one class painted the walls of the barber shop of the Union League Club, while others created murals in Chicago Public School buildings.

View of the Art Institute and Michigan Avenue, ca. 1912. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, IChi-61047.

During the early 1910s, a new art fund provided opportunities for murals in park field houses on the city’s South Side. Judge John Barton Payne (1855-1935) had established this fund by donating the $3,000 annual stipend he received for serving on the South Park Board of Commissioners. Through his fund, in 1911, Judge Payne arranged to have Art Institute students create a series of murals in the assembly hall of the Sherman Park field house. The project involved a class of eight advanced-level students who were studying mural painting under Norton and Stevens.

View of murals in Sherman Park field house assembly hall. Photo by James Iska.

The students produced the series of 20 murals during the spring and summer of 1912. Shortly after the project’s completion, a pamphlet was published about the artworks. It explains that the murals sought to focus on “American history, with a marked emphasis on the constructive phases in the history of the Middle West.” The park sat within a neighborhood that was largely filled with Eastern European immigrants, and Judge Payne and other park administrators believed that the murals would, in essence, serve as an American history lesson for the nearby residents who would frequent the park.

View of Sherman Park with tenement houses in the background, ca. 1910. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

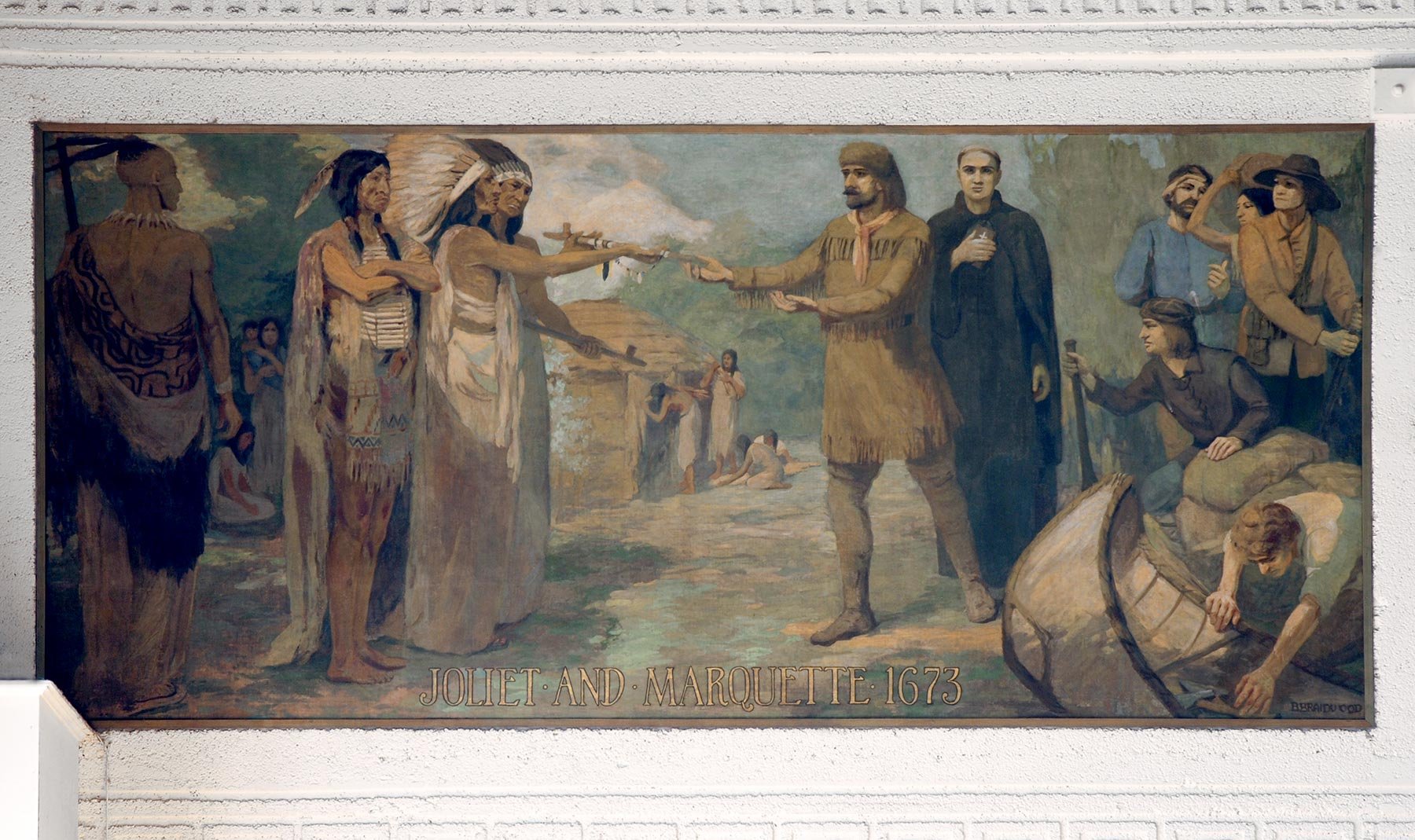

The pamphlet suggests that Sherman Park’s mural series was meant to provide “a chronological sequence of significant moments treated somewhat dramatically.” The various scenes include Columbus 1492, Plymouth 1620, and LaSalle and Tonty, 1682. When these artworks were created in the early 20th century, the theme of colonization in American history was revered, and such figures and scenes were considered heroic. As this approach to history is being reconsidered today, artworks such as the Sherman Park murals can provide insight into the culture of our city and the nation at that time.

Joliet and Marquette mural panel by Beatrice Braidwood. Photo by James Iska.

Beatrice Braidwood created the illustrations for this poem which appeared in Social Progress in 1919.

Four of the eight students who painted the Sherman Park murals were women. Beatrice Braidwood (1868– 1957)—creator of the Joliet and Marquette panel—was born in Philadelphia. She worked as an artist in New Jersey before moving to Chicago to study at the Art Institute. After completing her degree, Braidwood became a book and magazine illustrator and served as art editor of a journal called Social Progress.

Nouart Manoog Seron (1889-1956) painted the Columbus 1492 panel. Born in Turkey, Seron and her family were Armenian immigrants who briefly lived in Pennsylvania before settling in Joliet, Illinois. Finding information about this artist is somewhat tricky, in part because her name has been spelled several different ways. Listed as Nouart Seron in the Sherman Park pamphlet and several Art Institute publications, the artist’s first name sometimes appears as Nouvart, and her last name as Seron, Dzeron, and Seronian. She is memorialized as the subject of a painting called Nouvart Dzeron, A Daughter of Armenia by Ralph Clarkson, a talented artist who was one of her Art Institute instructors. According to the Art Institute of Chicago, when the young art student posed for the painting, she was wearing traditional Armenian garments that her grandfather had given her.

Nouvart Dzeron, A Daughter of Armenia. Art Institute of Chicago.

During her years at the Art Institute, Seron often exhibited her work and won awards. She also participated in masques that had been staged by her instructor, Thomas Wood Stevens. In the 1920s, Seron married an Armenian immigrant mathematics professor named Bedross (Peter) Koshkarian, and the couple moved to New Jersey. She continued to work professionally as an artist and occasionally performed on the radio as a mezzo soprano.

Lucille Patterson Marsh painting a billboard in New York City, ca. 1917.

The two other young women artists of the Sherman Park murals—Lucille Patterson and Anita Parkhurst—were good friends who both went on to have prolific careers as commercial artists. Lucille Patterson Marsh (1890-1978) was born in South Dakota and raised in Omaha, Nebraska by a divorced mother. Lucille began to study at the Art Institute in 1909, and in 1912, she was a recipient of the American Traveling Scholarship. Five years later, she married Allyn Ricker Marsh, a graduate of Williams College. (For at least a brief period, the couple and their young son were boarders in the Manhattan residence of Anita Parkhurst and her husband.) Especially well-known for creating idealized images of mothers and their children, Lucille Patterson Marsh produced advertisements that ran in such magazines as Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Cosmopolitan. In 1917, Lucille Patterson and Anita Parkhurst were both profiled in a nationally-syndicated article called “Pretty Girls Who Illustrate.”

Anita Parkhurst depicted in “Pretty Girls Who Illustrate,” The Buffalo Times, , January 21, 1917.

Anita Parkhurst Willcox (1892-1984) was born in Chicago to a well-to-do South Side family. After graduating from Hyde Park High School, she began her studies at the School of the Art Institute. Like her other female classmates, Parkhurst also often exhibited her work and won awards including a Frederick Magnus Brand Memorial Prize for Composition in 1912. After receiving her art degree, Anita Parkhurst moved to New York by 1916 and became quite successful as an illustrator. She became well known for depicting modern, fashionable young women, and her work appeared in numerous magazines, often as the cover art for popular publications including Collier’s and Saturday Evening Post.

Anita Parkhurst Willcox produced the artwork for this cover of Collier’s, January 15, 1921.

In 1918, Anita Parkhurst married Henry Willcox, a concrete engineer in the U.S. Quartermaster’s Office. Soon after their wedding, the young bride decided to interrupt her career and personal life to help support the U.S. troops during WWI. She went to France and performed vaudeville shows for soldiers fighting on the front lines. She often felt conflicted about the demands of her career and her role as a mother and wife, and in 1925, she wrote an unpublished book called Between Jobs and Babies. Her husband, Henry Willcox owned a prominent construction firm that built apartments for the New York City Housing Authority. Both he and Anita were long-time anti-war activists. After the couple visited China in 1952, the U.S. State Department confiscated their passports. They both suffered professionally from McCarthy-era politics. Despite her many challenges, Anita Parkhurst continued her work as an artist throughout her life. Of the Sherman Park female artists, she achieved the most acclaim.

Completed in 1916, John Warner Norton Hamilton Park mural series includes depictions of American statesmen, pioneers, and exquisite landscape scenery. Photo by James Iska.

Norton’s Liberty Bond Poster, 1918. Library of Congress.

In the mid- 1910s, as the Sherman Park students had begun pursuing their professional careers, John Warner Norton was hitting his stride as an artist. In addition to producing interior decorations for buildings designed by architects Purcell and Elmslie, he designed a poster for U.S. Liberty Bonds during WWI. A decade later, the nation was enjoying prosperity, and a major building boom was bringing him new mural opportunities. These included artworks for the Chicago Motor Club and Chicago Daily News Building. His prominence continued in the early 1930s, when he produced a mural for a county courthouse in Birmingham, Alabama. among other projects. Unfortunately, Norton’s career came to an abrupt halt when he became seriously ill in 1933 and died of stomach cancer the following year.

I hope I’ve whetted your appetite for Chicago’s mural history. If you’d like to learn more about this subject, I highly recommend A Guide to Chicago’s Murals by Mary Lackritz Gray. For a deeper dive on John Warner Norton check out the Illinois Historic Art Project website.