Deagan Building, 1770 W. Berteau Avenue. Though difficult to see in this photograph, the Deagan name stretches across the top of the clock tower. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

One of the of world’s major manufacturing hubs at the turn of the early 20th century, Chicago has many wonderful historic industrial buildings which, sadly, are now quickly disappearing. Ravenswood, which began as a North Side suburb in the late 1860s, developed a thriving industrial corridor along the Chicago and North Western Railway line a few decades later. Today, the Ravenswood community is committed to saving and reutilizing its historic industrial structures.

In the early 1900s, the Northwestern Elevated (now the CTA Brown Line) began offering passenger service to Ravenswood. The Deagan Building is visible just southeast of the “L” in this photograph. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

When I lived in Ravenswood many years ago, an old industrial complex located just down the street from my apartment on W. Berteau Avenue became one of my favorite buildings. I especially love how this beautifully-detailed “workhorse” fits into its mostly-residential neighborhood and how the tall clock tower that declares “This is the “Deagan Building,” can be seen from so many vantage points.

Advertisement for J.C. Deagan Inc., from Top Rung Tower Chime website.

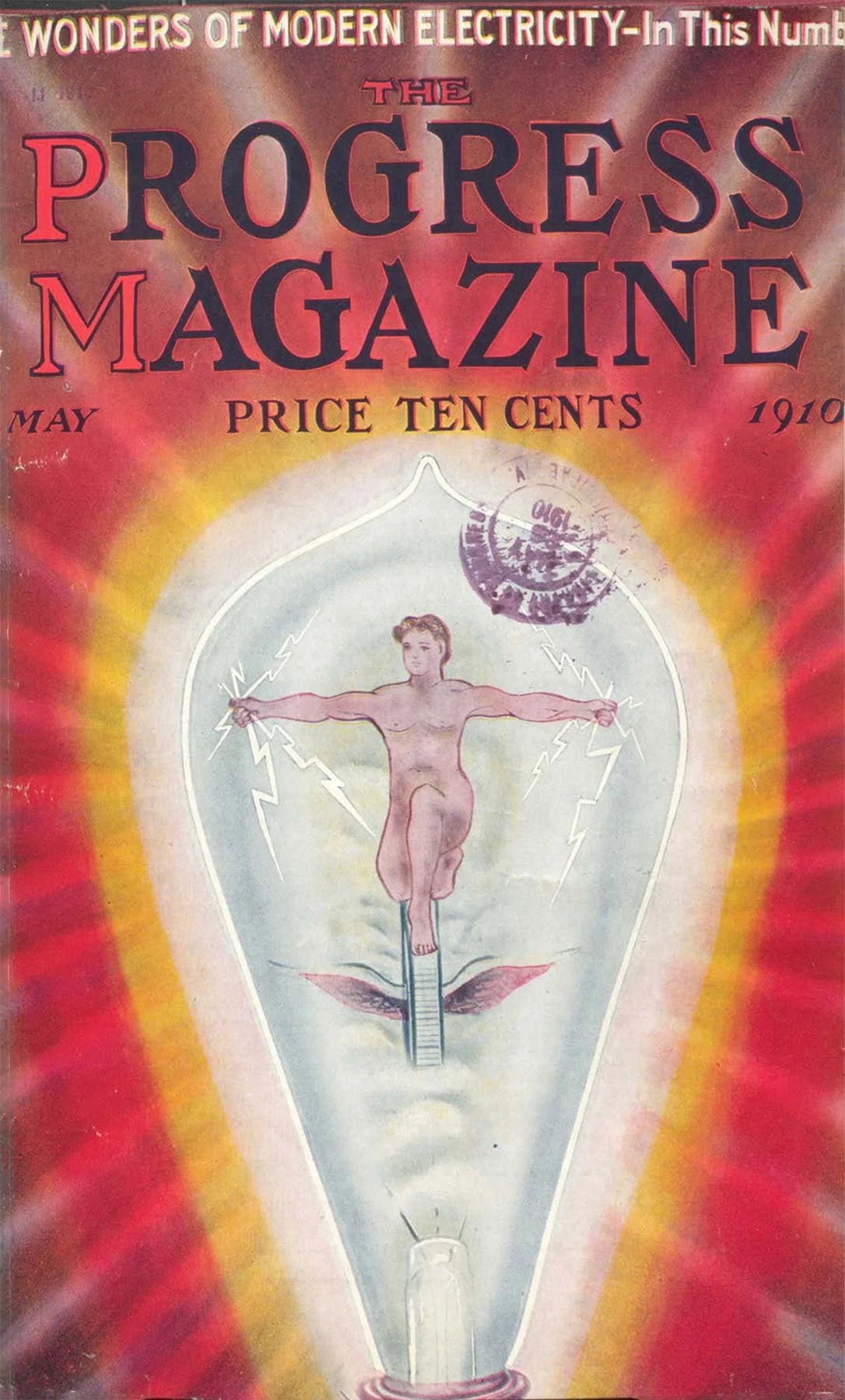

Although the handsome structure at 1770 W. Berteau Avenue served as the factory and headquarters for the J.C. Deagan Company for many decades, it was originally built by a publishing firm called the Progress Company. First incorporated in Chicago in 1908, Progress specialized in periodicals and books relating to metaphysical and psychological topics. The company published Progress Magazine, edited by Christian D. Larson, a leader in a spiritual “mind-healing” movement called “New Thought.” In addition to producing the monthly journal, Larson wrote many New Thought books, including several published by Progress Co., such as The Great Within, The Hidden Secret, and On the Heights.

The Progress Magazine, May, 1910.

In late 1909, when the Progress Company was quite busy producing books and magazines and even sponsoring a correspondence school called Self-Help University, the Chicago Tribune announced that the firm had plans to build a new plant at the corner of W. Berteau and N. Ravenswood avenues. The article includes a rendering of a three-and-a-half-story structure without a clock tower. The accompanying text explains that the Progress Co. building would include space for its publishing interests and correspondence school as well as a printing plant with a press and composing room and an electrotype foundry and power plant.

“The Progress Co.’s Building: New Buildings Mark Industrial Development in Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, December 12, 1909.

The Progress Company must have quickly decided that the proposed structure would not be large enough to accommodate the growing business because the following March, the City of Chicago issued a building permit to the company for a five-story structure that would be constructed for approximately $150,000. Frank E. Davidson, a partner in the firm of Patterson & Davidson, designed the building. Years later, Davidson told the Chicago Tribune he had been “trying for years to get owners to put their water tanks in ornamental towers," and that when he created the Progress Company’s W. Berteau Avenue building, “it was one of the pioneers in the movement to hide the unsightly roof tank.”

Close-up of the Deagan (Progress Company) Building Clock Tower. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Superintendent Frank E. Davidson provided a testimonial for Celery Compound as a cure for a condition known as grip. Chicago Tribune, February 12, 1899.

Born in Hillsborough, Iowa, Frank Eugene Davidson (1867-1931) graduated from Iowa State College with a degree in Civil Engineering in 1890. After briefly serving as assistant engineer to the Grand Canal Company in Arizona, Davidson moved to Chicago where he worked for various firms before establishing his own business as an engineer and contractor in 1894. Three years later, Davidson was appointed Superintendent of Sewers for Chicago’s Board of Local Improvements. While serving in this role, he helped prepare plans for Chicago’s famous intercepting sewerage system which diverted waste from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River via the new Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. Between 1899 and 1904, Davidson served as Architect and Engineer of Construction for the Western Electric Company.

In 1905, F.E. Davidson formed a partnership with William R. Patterson (1854-1916), an engineer, an inventor, and a director of Western Electric. The pair produced a number of buildings for Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works in Cicero before and after entering into private practice together. Patterson & Davidson quickly became successful as specialists in the design of industrial plants and complexes.

The Hawthorne Works Tower in Cicero, Illinois is the sole remaining vestige of Frank E. Davidson and William Patterson’s vast Western Electric Complex. Photo by Harman courtesy of Wikicommons.

The Progress Company operated out of its Ravenswood building for only a brief period. In 1912, the company declared bankruptcy and sold its factory to J.C. Deagan, Inc., for the reported sum of $220,000. John Calhoun Deagan, a professional clarinetist, had founded his musical instrument company in St. Louis in 1880. According to the National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Deagan’s first product was “an improvement upon the crude glockenspiel,” a German instrument made of metal keys that is similar to the xylophone but has a higher pitch. Moving his operation to Chicago in 1897, Deagan went on to produce a vast range of percussive instruments including xylophones, marimbas, hand bells, vibraharps, and various kinds of chimes including organ chimes and tubular bell chimes for carillons. For years, advertisements suggested that Deagan’s factory on W. Berteau and Ravenswood avenues was one of the largest musical instrument manufacturing concerns in the world.

J.C. Deagan, Inc. letterhead. From Made in Chicago Museum.

Frank E. Davidson remained a highly respected architect throughout the 1910s and 1920s. He served as president of the Illinois Society of Architects for several years and was also active in the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In the early 1920s, he was appointed to the State of Illinois’ Examining Committee for Architects, the body responsible for overseeing architect licensing. Throughout this period, Davidson’s firm had been restructured a few times. Frederick E. Lockwood, an architect who also specialized in industrial buildings, joined Davidson’s practice in 1913. The following year, the firm was split into Davidson & Lockwood, Architects, and Patterson & Davidson, Engineers. Davidson & Lockwood’s work includes the 1915 Fischer Furniture Plant at 400-418 W. May Street.

Fischer Furniture Building, 400-418 W. May Street. Photo by Cray M. Kennedy

Davidson was no longer affiliated with F.E. Lockwood by the time his engineering partner, William R. Patterson, died in 1916. Around that time, F.E. Davidson formed a new partnership with architect John W. Weiss (1868-1938), a German immigrant who had begun his career in the office of prominent early practitioner Edward Baumann. Davidson & Weiss practiced together until 1922. Among their many manufacturing buildings and warehouses is the Pyle-National Company Plant. Designed and built in 1916, the complex has several additions, some of which were produced by the original architects. The company manufactured headlights and generators for steam locomotives.

Pyle-National Company complex, 1334-1360 N. Kostner Avenue. Photo by Cray M. Kennedy.

After dissolving his partnership with Weiss, Frank E. Davidson maintained a solo practice until the end of his life. His projects of the mid-1920s include an enormous factory for the Olson Rug Company at 4000 W. Diversey Parkway. The sprawling complex of six-story-tall red brick and concrete structures was used as a mill and showrooms for Olson until 1965, when Marshall Field & Company acquired the behemoth and converted it into warehouse space. The 1.5 million square foot complex remained in use until around 2005, when Macy’s took over Marshall Fields.

The Olson Rug Company factory at 4000 W. Diversey later served as a gigantic warehouse facility for Marshall Field & Company. Photo by Cray M. Kennedy.

Now called the Fields, the old factory/warehouse complex is a major mixed-use development. Photo by Cray M. Kennedy.

When Macy’s vacated the site, preservationists feared that the vast Davidson-designed complex would fall to the wrecking ball, as so many other large industrial structures have in Chicago. Fortunately, a group of developers purchased the 21-acre campus in 2014, and the old factory/warehouse is being converted into a mixed-use project with loft apartments, shops, and restaurants, and other businesses.

Like the Olson Rug Factory/Marshall Field Warehouse, the Deagan Building had a long history as an industrial structure. The Deagan family owned and operated their musical instrument company until 1978, when they sold out to Slingerland, another successful Chicago instrument company. Yamaha bought the Deagan division of Slingerland in the early 1980s. Although Hayes Properties acquired the Deagan Building in 2008, the new ownership didn’t sever the structure’s important connection to percussive instrument-making. In 1980, Gilberto Serna, a former Deagan Company employee, established the Century Mallet Instrument service in the building’s second story, a space that previously served as Deagan’s machine shop. Century Mallet, which tunes, repairs, and restores percussive instruments, including those originally made by J.C. Deagan, Inc., continues operating from the building to this day.

Entrance to the Deagan Building. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

It’s so nice to see a more-than-century-old industrial building that is so well-used and well-loved today. I hope many other great structures like this one will have the chance to stand the test of time.