Sunset Point, Eagle River, Wisconsin, designed by Nedved & Kimball. Courtesy of Wisconsin State Historic Preservation Office, AHI # 21559, 2005.

“This Woman Has Both a Career and a Husband: She and He Forge to the Front of Architects,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 6, 1928, p. 13.

When I’m doing historic research, I often get distracted by an interesting topic that has nothing to do with the matter at hand. That was the case recently when I was researching a mid-1920s luxury apartment building and stumbled upon a brief news piece announcing that Nedved & Kimball, husband and wife architects, had opened an office in the Marquette Building. A quick search of the on-line historical Chicago Tribune filled in more details about Rudolph James Nedved (1895-1971) and his fascinating wife, Elizabeth Kimball Nedved (1897-1969). An article about their firm, “This Woman Has Both a Career and a Husband,” includes a head shot of Elizabeth and describes her as “one of the few active women architects of America.” I’ve since done a deeper dive to learn more about Elizabeth Kimball Nedved, and I’d like to share what I’ve found with you.

The oldest child of Ernest and Jessie Kimball, Elizabeth Kimball was born in Chicago in 1897. Her father was the owner of Kimball’s, a restaurant that is said to be the nation’s first cafeteria. According to William Rice, a former food and wine critic for the Chicago Tribune, Kimball opened a restaurant in the 1890s that combined “convenience and low prices,” luring “thousands of office workers from their desks at lunch time and a host of imitators along what became known as ‘Toothpick Row’ in the Loop.” Kimball’s success soon led to a second cafeteria, and allowed him to move his family to the North Shore. Elizabeth Kimball grew up first in Winnetka and then in Glencoe. As a student at New Trier High School, one of her teachers suggested a career as a professional artist. After graduating, she attended the Church School of Art at 606 S. Michigan Avenue in Chicago from 1916 to 1918, specializing in interior decorating.

“Display Advertisement” for Church School of Art, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1919, p. D9

After completing art school, Kimball worked as an interior decorator for Marshall Field & Co. However, she was dissatisfied, so she attended Northwestern University for a year. While there, she worked as a draftsman for architects Tallmadge & Watson. The position likely fostered her desire to become an architect, and in 1921, Elizabeth Kimball began pursuing a bachelor’s degree in architecture at the University of Illinois. After a year or two, she transferred to the Armour Institute.

The Cycle, Armour Institute Yearbook, 1925.

According to the 1928 Tribune article, when Elizabeth Kimball began studying architecture at the Armour Institute, she “was given a drafting table right next to an affable young man named Rudolph Nedved” who had “a way of smiling at her that made her know she was going to find architecture a highly congenial study.” Born in Bohemia, Rudolph James Nedved immigrated to Chicago with his family during childhood. He graduated from Crane High School, and worked as a draftsman for the Western Electric Company prior to receiving a degree in architecture from the Armour Institute in 1921.

The Cycle, Armour Institute Yearbook, 1925.

Rudolph Nedved soon began teaching architectural design at Armour. He won the 1923 Annual Traveling Scholarship Competition (sponsored by the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club). That summer, the Kimball family planned a trip to Europe to coincide with Rudolph’s time abroad. In September, Rudolph and Elizabeth were married in London’s City Temple Church. More than 30 of the couple’s Chicago friends and family attended their wedding in England.

“Ca’ d’Oro Venice,” Elizabeth Kimball Nedved’s watercolor of the famous Palazzo Santa Sofia was published in Pencil Points, Vol. VIII, No. 4, April 1927.

Austin Presbyterian Church, Rudolph and Elizabeth Nedved Architects, 1927. Chicago Architectural Sketch Club Collection. Ryerson & Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago.

Elizabeth received her architectural degree from the Armour Institute in 1925. The following year, Rudolph was elected President of the Chicago Architectural Sketch Club. The club soon organized a watercolor class with Elizabeth as instructor. Elizabeth displayed her work in several exhibits, including the International Watercolor Exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. Also in 1926, the couple opened their own architectural office. (Rudolph J. Nedved had previously worked for the firms of Tallmadge & Watson and Schmidt, Garden & Martin.) Their firm was generally known as Nedved & Kimball architects.

Nedved & Kimball soon produced several Revival style residences for prominent clients. In 1927, they designed a French Normandy style house for Sunset Point, the summer estate of Chicagoan M. J. Tennes in Eagle River, Wisconsin. That same year, the Chicago Tribune reported that, despite the strenuous objections of several architects, Mrs. Elizabeth Nedved had been admitted as “the first woman member of the American Institute of Architects.”

The second annual Woman’s World’s Fair was held at the Chicago Coliseum in 1927. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, DN-0075467.

Elizabeth and a few female colleagues began collaborating to bring public awareness to the small, but growing number of women architects in Chicago. Elizabeth Nedved, Juliette Peddle, and Catherine Heller created an exhibit for the second annual Woman’s World’s Fair, a 10-day pageant held in the Coliseum, the city’s major arena building at 1513 S. Wabash Avenue. The trio of architects created a display that included a model nursery and kitchen. This initiative helped inspire the 1927 formation of the Women’s Architectural Club of Chicago.

The Nedveds owned the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Glasner House in Glencoe for over 40 years. Photo courtesy of Vinci Hamp Architects.

Elizabeth Kimball Nedved received her architectural license in 1928. She gave birth to a son, Kimball Nedved, in October of that year. Also in 1928, the Nedveds purchased the Glasner House, a 1906 Frank Lloyd Wright-designed residence in Elizabeth’s home town of Glencoe, Illinois. Elizabeth and Rudolph raised their family – which would grow to include another son and a daughter – in the Glasner House, making minor alterations, such as improving the unfinished basement, to provide more space for their family of five. The Nedveds owned the Glasner House for over 40 years.

Avery Coonley School, Downers Grove, Illinois designed by Hamilton, Fellows & Nedved with architect Wauldren Faulkner. Photo courtesy of Jean Follett.

By the end of 1928, the Nedveds had formed a partnership with architects John Hamilton and William Fellows after the recent dissolution of Perkins, Hamilton & Fellows. Dwight Heald Perkins was known for progressive school designs and his firm of Perkins, Hamilton & Fellows had been specializing in educational buildings for about 20 years. Hamilton, Fellows & Nedved continued that tradition. (Elizabeth Kimball Nedved was considered a silent partner in the firm.) Hamilton, Fellows & Nedved collaborated with architect Waldron Faulkner on the Avery Coonley School in Downers Grove. As historian Jean Follett explains in the National Register nomination for Coonley School, with its open courtyard, flexible and “well-thought-out floor plan,” homey Arts & Crafts style details, and classrooms looking onto the spacious wooded site, the lovely 1929 building provided a nurturing learning environment. Elizabeth Kimball Nedved remained professionally active during the early 1930s. She was elected President of the Women’s Architectural Club in 1931, and Vice-President of the group the following year. Although Hamilton, Fellows & Nedved’s workload diminished considerably during the Depression, one of their best known projects, Wyandotte School in Kansas City, Kansas, was completed in 1937.

Wyandotte High School, Kansas City, Kansas. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

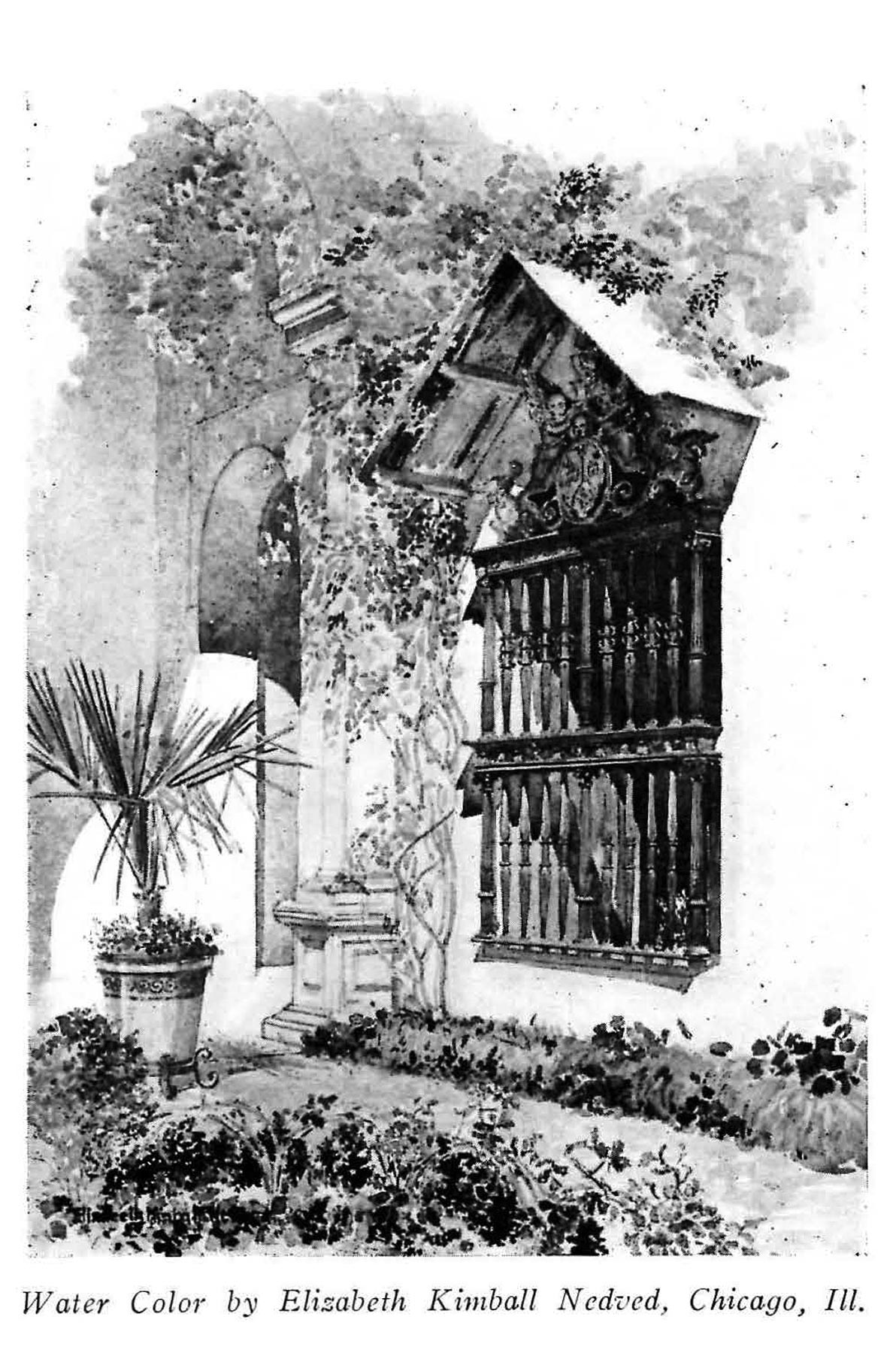

Watercolor by Elizabeth Kimball Nedved, Pencil Points, Vol. VI, No. 3, August 1925.

In 1937, when Rudolph Nedved accepted a position as an adviser for the United States Housing Authority in Washington, DC, the family relocated to Virginia for several years. During WWII, Elizabeth found work as a marine engineer for the US Navy, Bureau of Ships. The Nedveds returned to their Glencoe home sometime before 1950. Rudolph went on to join the firms of Fugard, Orth & Associates for 17 years, and Schmidt, Garden & Erikson, at the end of his life. It is unclear whether Elizabeth continued working professionally in the 1950s. However, she requested re-admittance to the AIA in the early 1960s, and was reinstated as a member of the organization.

Elizabeth Kimball Nedved’s contributions to architecture, the role she played in particular projects, and her full body of work remain unclear. I hope more information about her will come to light. Regardless, there is no doubt that this talented architect and artist, active organization member, wife, and mother was quite a trail-blazer.