View from the Park Gables courtyard looking towards Indian Boundary Park. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

Everyone knows that living near a park can enhance the value of a home. But an apartment building that is seamlessly connected to a park is truly a rare find. One of the few local examples is a group of four historic multi-family buildings that edge Indian Boundary Park in Chicago’s West Ridge neighborhood. The realty firm of Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz developed these buildings and gave each a fitting name— the “Park Crest,” “Park Manor,” “Park Castles,” and the “Park Gables.”

Park Gables Cooperative Building. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

I am fortunate to have several friends and family members who live in the Park Gables, a double courtyard building at 2438-2484 W. Estes Avenue. Check out this fabulous three-bedroom unit currently on the market in the Park Gables. With its slate roof, half-timbered projecting gabled bays, and tall casement windows, the Park Gables is a fine example of the Tudor Revival style. Erected in 1927, this was the fourth of Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz’s ensemble of Indian Boundary Park cooperatives. Predating the Indian Boundary Park Field House by two years, the Park Gables likely inspired architect Clarence Hatzfeld’s English Tudor style park building.

Rendering by Roffe Beman of the Clarence Hatzfeld-designed Indian Boundary Field House, ca. 1930. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

During the late 1920s, Indian Boundary Park was in the midst of an expansion project. First established in 1915 by the Ridge Avenue Park District (one of 22 independent park commissions that would later be consolidated into the Chicago Park District) Indian Boundary Park was originally about seven-and-a-half acres in size. The earliest part of the site was located near Lunt Avenue and Rockwell Street encompassing what is now the west side of the park. The Ridge Avenue Park Board hired Evanston landscape gardener and horticulturalist Richard Gloede to design the green space, and by the summer of 1916, the new park had lawn, trees, shrubs, and a small frame field house with open verandas on each side. Within a short time, the park district installed a playground near the field house. (The original field house sits roughly on the site of today’s playground.)

View of original Indian Boundary Park field house and playground, ca. 1927. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

Chicagoans Earl G. Gubbins and Allan E. McDonnell formed a real estate firm around 1920. Sometimes referred to as the Sheridan Real Estate Improvement Association, Gubbins & McDonnell operated out of an office at 6505 N. Sheridan Road. First serving mainly as real estate brokers, the firm soon began developing its own buildings. Gubbins & McDonnell built several lovely bungalows near Indian Boundary Park, including Allan McDonnell’s own home at 2453 W. Coyle Avenue. But it was co-operative apartment buildings that quickly became the firm’s specialty. Tenant-owned co-operative apartment buildings were relatively rare in Chicago until the early 1920s, when Illinois law allowed for the formation of corporations specifically to purchase and improve real estate. As Neil Harris explains in Chicago’s Apartments: A Century of Lakefront Luxury, once such real estate corporations were permissible, co-operative ventures quickly became “a dominant type in the luxury market.”

“Display Ad 15,” Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1925, p. 16.

While many of the city’s spacious and well-appointed co-operatives were located on the lakefront near Lincoln Park, Gubbins & McDonnell believed that there was a market for such buildings in other North Side neighborhoods, including West Ridge. The firm decided to erect high-quality buildings overlooking Indian Boundary Park to appeal to middle-class Chicagoans who might not want—or might not be able to afford—to buy a house or a more expensive lakefront co-operative apartment. Therefore, Gubbins & McDonnell acquired property bordering the new eastern boundary of Indian Boundary Park and developed both the Park Manor at 2415-2437 W. Greenleaf Avenue and the Park Crest at 2420-2434 W. Lunt Avenue in 1925.

“Display Ad 16,” Chicago Tribune, January 10, 1926, p. 17.

Gubbins & McDonnell hired architect James F. Denson to design their Park Manor and Park Crest co-operative buildings. Although both Chicago’s Historic Resources Survey and the AIA Guide to Chicago Architecture attribute the Park Crest to Denson, these sources credit architect Melville Grossman with the Park Manor’s design. The Park Manor attribution is apparently based upon the Chicago building permit, on which “Grossman” —no first name—is listed as architect. Chicago Tribune advertisements of the period, however, indicate that Denson designed both buildings. Furthermore, architect Melville Grossman was only a young boy in the mid-1920s.

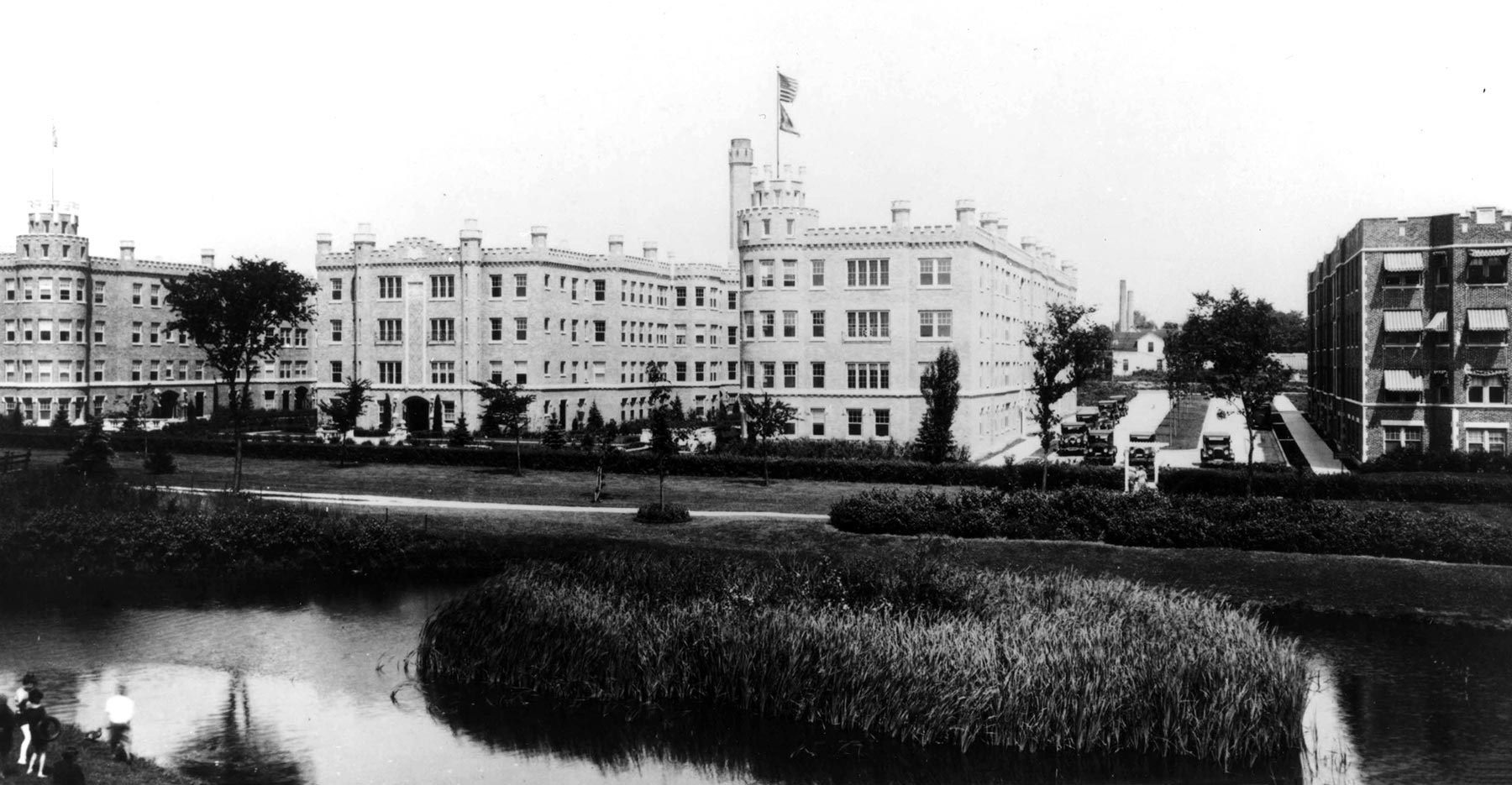

View of Park Castles, Park Manor, and east end of Indian Boundary Park, ca. 1930. Courtesy of Rogers Park West Ridge Historical Society, P045-0101.

By early 1926, the sponsor of the Indian Boundary co-operatives had added a third partner, Irvin A. Blietz. At that time, the firm of Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz was working on another nearby building, the Park Castles at 2416-2458 W. Greenleaf Avenue. The real estate investors allocated a project budget of approximately $600,000 for the Park Gables.

Like the Park Manor, the design of the Park Castles has long been misattributed to an architect other than Denson. As the permit lists J. E. Jensen as project architect, historians have assumed that the building was produced by architect Jens J. Jensen. Responsible for such fine1920s buildings as the Guyon Hotel, Jens J. Jensen is sometimes confused with the more famous landscape designer, Jens Jensen. While the timing seems feasible an article and display ads that ran in the Chicago Tribune in 1926 substantiate that J.F. Denson (not Jensen) designed the whimsical Park Castle building. (Perhaps a City employee had heard the name incorrectly when filling out the building permit.)

“Display Ad 46,” Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1926, p. B6.

St. Peter Armory, St. Peter, MN. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

Born in Virginia, James Fletcher Denson (1865-1927) was the stepson of Thomas H. Powell, a draftsman in the architect’s office of the U.S. Treasury Department. Denson began his career in the office of Washington, DC architect Alfred B. Mullett. Denson worked his way up from draftsman to partner of A.B. Mullett & Co. prior to establishing his own firm in the early 1890s. He briefly partnered with architect F.T. Schneider, and then continued practicing independently in Washington, DC. Sometime before 1909, Denson moved to Minnesota, where he managed the St. Paul office of Chicago architects Postle & Mahler. He soon became a partner in the firm. Around 1913, he left Postle, Mahler & Denson and opened his own office, producing fine Revival style buildings such as the St. Peter Armory in St. Paul. Denson relocated to Chicago around 1918. He lived on the North Side and had an architectural office downtown. Denson’s local work includes the 1925 Chicago Journeyman Plumbers’ Union Building at 1340 W. Washington Boulevard.

Black bears at Indian Boundary Park Zoo, ca. 1935. Courtesy of Rogers Park West Ridge Historical Society, R002-0103.

True to its name, with its engaged towers, crenellated parapets, and an original moat-like fountain, the Denson-designed double courtyard building emulated a Medieval English castle. Completed in the spring of 1926, the Park Castles overlooked Indian Boundary Park’s eastern extension, which included a small lagoon that had been part of Richard Gloede’s landscape extension plan. By this time, Indian Boundary Park also had its own small zoo with a major attraction, a black bear named Teddy who loved to eat canned salmon and chocolate cake. (The zoo later acquired other animals including additional black bears.)

Following the success of the three co-operatives that overlook the eastern edge of Indian Boundary Park, Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz purchased a large parcel on W. Estes Avenue at the northeast corner of the park. Denson prepared plans for the Park Gables and the city issued a building permit for the project on January 5, 1927. A month-and-a-half later, in an article entitled “Co-op at Indian Boundary Park Resembles Club,” the Chicago Tribune suggested that the substantial $1,150,000 project would result in “one of the city’s greatest co-operative apartment building developments.” The fine double courtyard structure featured 73 spacious four-, five-, and six-room apartments. The building included kitchens with electric refrigerators and incinerators, and indoor club facilities with a nine-hole putting green and a “luxurious Pompeian swimming pool.”

Indoor Swimming Pool at the Park Gables. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz wanted the Park Gables to have the same kind of seamless connection with Indian Boundary Park that the other buildings had. But plans were underway for the extension of W. Estes Avenue from N. Rockwell Street to N. Western Avenue. On June 27, 1927, several area residents attended a meeting of the Ridge Avenue Park Board along with Mr. James P. McCarthy, a representative of Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz. The group presented a petition protesting against the extension of Estes Avenue. Although there is no written record of the Park Board’s official decision, there is no doubt that the protesters’ request was granted in part. The paved Estes Avenue roadway extends only one-half block east of N. Rockwell, and the lawn of the park has always stretched to the front yard of the Park Gables.

Panoramic view of Indian Boundary Park with Park Gables, Park Castles, and Park Manor in the distance. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz published an early marketing pamphlet for the Park Gables suggesting that “families of average means” could “become owners of “up-to-the-minute apartments, ideal in every respect.” The pamphlet goes on to say: “These apartment homes are being purchased by architects, physicians, as well as businessman who have ‘arrived,’— or who are on the road to success.” Apparently, Irvin Blietz fit this profile, as he and his wife and son were the owners and residents of a unit at 2460 W. Estes Avenue.

Rendering from Park Gables Marketing Brochure, ca. 1927. Gubbins, McDonnell & Blietz.

Indian Boundary Park has experienced some changes over the years. The most conspicuous is that its zoo closed in 2013, and has since been replaced with a Nature Play Area. However, the park is still a lovely and vibrant 13-acre green space, and the beautifully-maintained Park Gables has never lost its allure.

View of Park Gables courtyard looking north. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

As Gubbins, McDonnell, & Blietz had advertised in the 1920s, the building remains a place where residents can “look out at trees instead of brick walls.” They can “see children playing happily and safely instead of hearing the noise of traffic and breathing the exhaust of automobiles.” And they can enjoy “all of the convenience of city life,” in spectacular apartments that are truly homes.